Training hard is useless if you are fighting against your own biology. You put in the hours and the effort, but without a foundational understanding of sports science, you are likely leaving gains on the table or worse, inviting injury. If you’ve ever wondered why your squat numbers have stalled or why your lower back always aches after a session, the answer usually isn’t a lack of strength; it is a lack of proper biomechanics.

This guide is not a dry academic textbook; it is an actionable playbook. Forged from over 15 years of in-the-trenches coaching experience and a graduate-level background, I have stripped away the complexity to give you exactly what works. This is Sports Science 101, designed specifically for the dedicated fitness enthusiast in Dubai to translate the complex science of human movement into tangible, pain-free results.

In this 5-step blueprint, we will decode the physics of lifting to help you injury-proof your body and master the “big three” lifts. We will move beyond generic advice and apply physiological principles specifically adapted to the unique demands of the UAE’s climate. It’s time to stop guessing, master your mechanics, and finally train with purpose.

Step 1: The Foundations – Demystifying Exercise Science

What is biomechanics? (and why it’s not just for pro athletes)

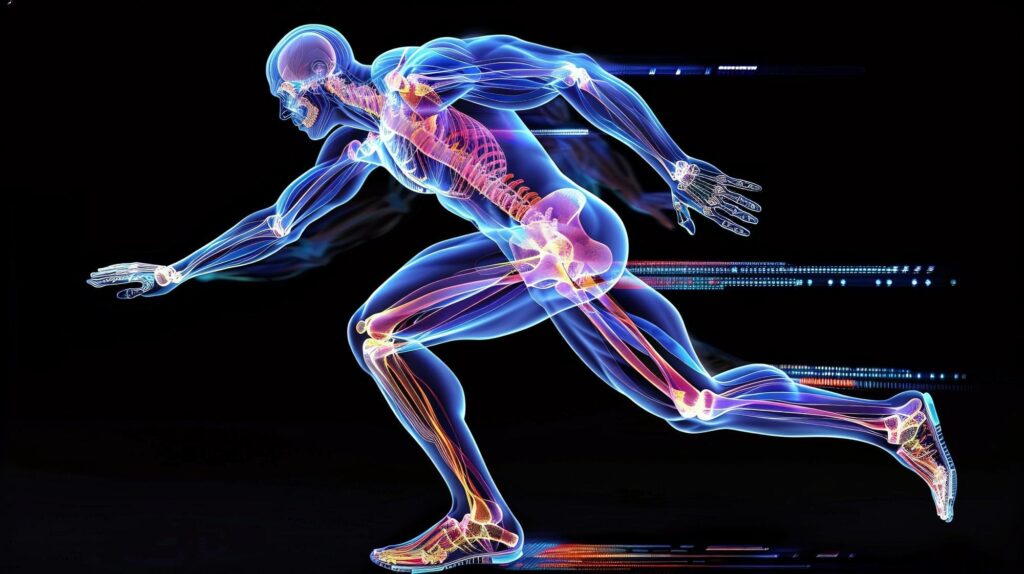

Biomechanics in fitness is the study of how forces interact with your body to produce movement. Think of it as the official owner’s manual for your body. It explains how your levers (bones), pulleys (muscles), and joints are designed to work together for maximum efficiency and safety. When you move with poor biomechanics, you’re not just risking injury; you’re wasting energy and leaving potential gains on the table. Understanding these principles is the first step from simply exercising to training intelligently. This foundational knowledge is supported by extensive research in the field of exercise biomechanics for health.

What is exercise physiology? (how your body actually adapts and improves)

Exercise physiology is the science of how the body responds and adapts to the stress of physical activity. If biomechanics is the owner’s manual, physiology explains how to upgrade your engine. It covers everything from how your body creates energy to fuel a heavy lift, to how your muscles repair and grow stronger after a workout, to how your cardiovascular system improves over time. By understanding the basics, you can structure your training and recovery to drive specific adaptations, ensuring your hard work leads to real, measurable progress. The foundational principles of exercise physiology are the bedrock of every effective training program.

The kinetic chain: your body’s interconnected highway

The kinetic chain describes how your interconnected segments—like your ankles, knees, hips, and shoulders—work together to produce coordinated movement. A problem in one area can have a significant impact elsewhere. Think of it like a traffic jam on Sheikh Zayed Road; a single stopped car can cause issues for miles.

Exercises can be categorized as open-chain (where the hand or foot is free to move, like a leg curl) or closed-chain (where the hand or foot is fixed, like a squat). A balanced program includes both to build a resilient body.

For example, I once coached a client who had persistent knee pain during squats for years. We didn’t focus on his knee; we worked on his poor ankle mobility. By improving his ankle’s range of motion, we unlocked his entire lower body kinetic chain, and his knee pain vanished within weeks. This is the power of understanding that your body is a single, interconnected system.

Force, torque, and leverage: simple physics for smarter lifting

You don’t need a physics degree to lift effectively, but understanding these three concepts will transform how you approach your training:

- Force: This is the simple push or pull you apply to a weight. Your goal is to apply force as efficiently as possible in the desired direction.

- Leverage: Your bones act as levers. Understanding this allows you to use a small effort to move a much larger weight by optimizing your body position.

- Torque: This is the rotational force created at a joint (like your knee or shoulder). Controlling torque is the key to both generating power and preventing injury. When you squat, for instance, creating external rotation torque at the hips helps activate your glutes and stabilize your knees.

By mastering these concepts, you can create optimal joint angles for lifts like the squat and deadlift, allowing you to maximize the force you produce while minimizing harmful stress on your joints.

Step 2: The Science of Safety – Building an Injury-Proof Body

Identifying and correcting common muscle imbalances

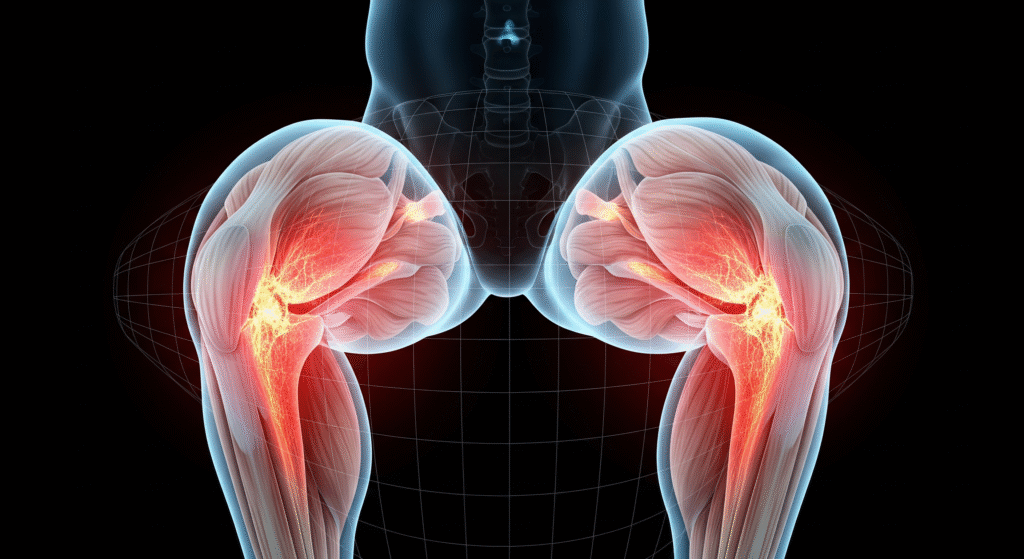

Muscle imbalances occur when one muscle group becomes significantly stronger or more active than its opposing group, disrupting the harmony of your kinetic chain. For many urban professionals in Dubai, long hours spent sitting at a desk lead to a predictable pattern: overactive, tight chest muscles and hip flexors, paired with underactive, weak upper back muscles and glutes.

When you load these imbalances with heavy weights, you aren’t training; you are compensating. Your body will twist, arch, or collapse to complete the rep, placing dangerous stress on your joints rather than your muscles.

The importance of screening before you load

You wouldn’t drive a car with misaligned wheels, yet many people squat with misaligned hips. The “scientific” approach to safety isn’t just about lifting form; it starts before you even touch the bar.

To truly injury-proof your body, you need to visualize these invisible dysfunctions. This is done through specific movement screens, such as the Overhead Squat Assessment. This diagnostic tool allows you to see exactly where your mobility restricts you. Whether it’s knees caving in (valgus) or a lower back arching excessively.

Head over to my Pain-Free Training guide for a step-by-step Overhead Squat Assessment to spot your own movement roadblocks.

Once you have identified your specific imbalances through screening, generic warm-ups are no longer enough. You need to apply biomechanics to your preparation. This introduces the concept of Corrective Exercise—specific, targeted movements designed to “release” tight areas (like using a couch stretch for hip flexors) and “activate” weak ones (like using glute bridges for dormant hips).

By addressing these issues proactively, you stop forcing your body into unnatural positions. This doesn’t just prevent injury; it mechanically optimizes your body to lift heavier weights with less effort.

The hidden dangers of inefficient form and repetitive strain

Poor biomechanics don’t just look sloppy; they create “force leaks” that rob you of strength and stall your progress. Every repetition with suboptimal form reinforces a faulty movement pattern, leading to repetitive micro-trauma. This damage accumulates over time and eventually manifests as chronic issues like tendonitis, joint pain, or a sudden, acute injury.

I once worked with a client suffering from chronic shoulder pain during his bench press. He was strong, but his technique was off. He wasn’t retracting his shoulder blades to create a stable platform. By teaching him this simple biomechanical fix—squeezing his shoulder blades together as if holding a pencil between them—we stabilized the joint. The pain disappeared, and his bench press numbers started climbing again. This highlights why a proper dynamic warm-up is crucial; it’s not just about getting warm, it’s about preparing your brain and body for efficient, safe movement.

The role of mobility and stability in injury prevention

Mobility and stability are two sides of the same coin, and you need both to be resilient against injury.

- Mobility is the ability of a joint to move actively through its full range of motion.

- Stability is the ability to control that movement and resist unwanted motion.

For example, good hip mobility allows you to reach full depth in a squat. However, good core stability is what prevents your lower back from rounding at the bottom of that squat. One without the other is a recipe for disaster.

Add these to your warm-ups:

- Essential Mobility Drills: Hip 90/90s, Cat-Cow, Thoracic Spine Windmills.

- Essential Stability Drills: Plank variations, Bird-Dog, Dead Bug.

Progressive overload: the principle of getting stronger, safely

Progressive overload is the fundamental principle of making long-term progress. It means gradually increasing the demands placed on your body over time. However, the biggest mistake people make is thinking it only means adding more weight to the bar.

You can also achieve progressive overload by:

- Increasing the number of repetitions.

- Increasing the number of sets.

- Decreasing your rest time between sets.

- Improving your form and control over the weight.

Adding weight before your biomechanics are solid is one of the fastest ways to get injured. True strength is built by earning the right to add more weight, not just forcing it.

Sample 4-Week Overhead Press Progression:

- Week 1: 3 sets of 8 reps @ 40kg

- Week 2: 3 sets of 9 reps @ 40kg

- Week 3: 3 sets of 10 reps @ 40kg

- Week 4: 3 sets of 8 reps @ 42.5kg

Step 3.1: Movement masterclass part 1: a biomechanics breakdown of the squat

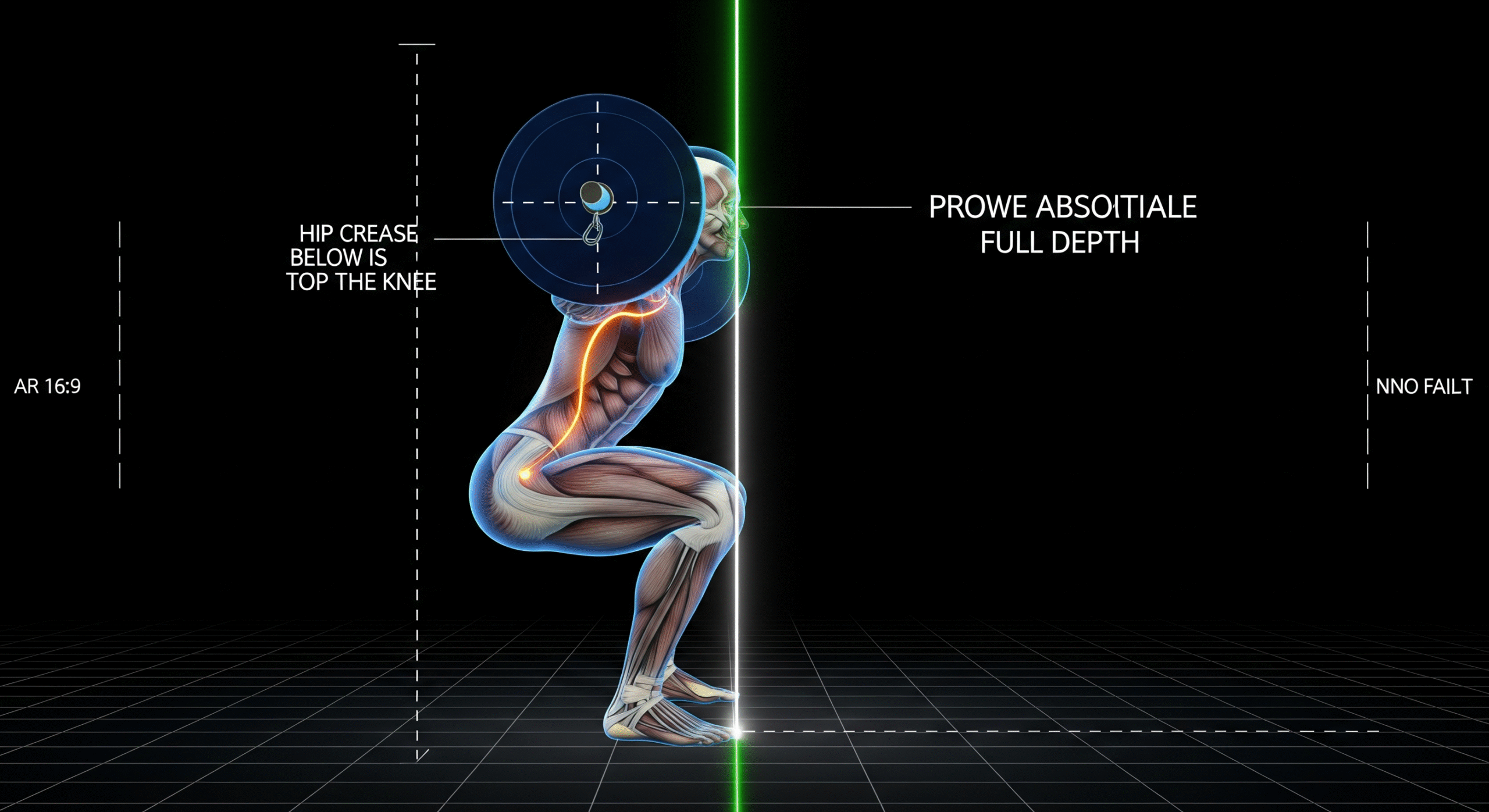

Anatomy of a perfect squat: joint angles, bar path, and pressure

A perfect squat is a symphony of coordinated movement. Let’s break it down from the ground up:

- Foot Placement and Pressure: Establish a “tripod foot” by grounding your heel, the base of your big toe, and the base of your little toe. This creates a stable base of support.

- Knee Tracking: As you descend, your knees should track in line with your toes. This ensures the torque at the knee joint is managed safely.

- Hip Crease: Initiate the movement by breaking at the hips and knees simultaneously, sending your hips back and down. Aim for your hip crease to go below the top of your knee for a full-depth squat.

- Bar Path: The barbell should travel in a straight vertical line directly over your mid-foot throughout the entire lift. Any deviation forward or backward indicates an inefficiency or imbalance.

Solving common squat mistakes: knee valgus, ‘butt wink’, and rising chest

Every common squat fault has a biomechanical cause and a corrective solution.

- Knee Valgus (Knees Caving In):

- What it is: Your knees collapse inward during the squat.

- Cause: Often caused by weak gluteus medius muscles (hip abductors).

- The Fix: Banded lateral walks and placing a mini-band around your knees during warm-up squats to teach you to push your knees out.

- ‘Butt Wink’ (Posterior Pelvic Tilt):

- What it is: Your lower back rounds and your pelvis tucks under at the bottom of the squat.

- Cause: Typically due to ankle mobility restrictions or a lack of motor control.

- The Fix: Ankle mobility drills (like knee-to-wall tests) and goblet squats to a box to practice maintaining a neutral spine.

- Chest Falling Forward:

- What it is: Your torso pitches forward excessively on the way up.

- Cause: Often a sign of a weak upper back or poor core bracing.

- The Fix: Paused squats to build control and front squats, which force a more upright torso position.

Squat variations and their biomechanics differences

The type of squat you choose changes the leverages and muscle recruitment.

| Variation | Bar Position | Torso Angle | Primary Muscles Targeted | Best For |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| High-Bar | On top of the trapezius muscles | More upright | Quadriceps | Bodybuilding, General Strength |

| Low-Bar | Across the rear deltoids | More forward lean | Glutes, Hamstrings, Lower Back | Powerlifting |

| Front Squat | Resting on the front of the shoulders | Most upright | Quadriceps, Upper Back, Core | Athletic Performance |

Your step-by-step checklist for a safer, stronger squat

- Stance and Foot Pressure: Set your feet shoulder-width apart and establish your stable “tripod foot.”

- Grip and Upper Back: Grip the bar firmly. Pull it down into your back to create a stable shelf and engage your lats.

- The Walkout: Take 2-3 deliberate, controlled steps back from the rack.

- The Brace: Take a deep 360-degree breath into your belly and brace your core as if you’re about to take a punch.

- The Descent: Break at your hips and knees, keeping your chest up and knees tracking over your feet.

- The Ascent: Drive up by thinking “chest up” and pushing the floor away, maintaining your balance over your mid-foot.

Step 3.2: Movement masterclass: a biomechanics breakdown of the deadlift

The hip hinge: mastering the most critical movement pattern

First, let’s be clear: the deadlift is not a squat. A squat is a knee-dominant movement. A deadlift is a hip-dominant movement pattern called a hinge. Mastering the hip hinge—the ability to bend at the hips while maintaining a flat, neutral spine—is non-negotiable for back health, both in the gym and in life.

To learn the pattern, try the “wall tap” drill. Stand about a foot away from a wall, facing away from it. Keeping a slight bend in your knees, push your hips straight back until your glutes tap the wall, all without rounding your lower back. That is a hip hinge.

Biomechanic differences: conventional vs. sumo deadlifts

The best stance for you depends largely on your individual anatomy, particularly your hip structure and femur length.

- Conventional Deadlift:

- Stance: Feet are hip-width apart, with hands gripping the bar just outside the shins.

- Demands: Places greater stress on the spinal erectors and requires more hip mobility. Features a longer range of motion.

- Sumo Deadlift:

- Stance: Feet are very wide, with hands gripping the bar inside the legs.

- Demands: Allows for a more upright torso, placing greater stress on the hips and quads. Features a shorter range of motion.

Neither is inherently superior; the right choice is the one that allows you to maintain a neutral spine and lift most effectively based on your body’s leverages.

The 3 most common deadlift faults that cause back pain

In my 15 years of coaching, I’ve seen these three errors cause more preventable injuries than any others.

- Rounding the Lumbar Spine (Lower Back):

- Cause: Initiating the lift with your back instead of your legs, or setting up with the bar too far away from your shins.

- The Fix: Before you lift, “pull the slack out” of the bar. This means pulling up on the bar until it clicks against the plates, engaging your lats and creating full-body tension to lock in your flat back.

- Hips Shooting Up First:

- Cause: Weak quads or improper timing, causing you to turn the lift into a stiff-leg deadlift.

- The Fix: Focus on the cue “push the floor away” with your legs, as if you are doing a leg press. Your hips and shoulders should rise at the same rate.

- Hyperextending at Lockout:

- Cause: A misguided attempt to finish the lift by aggressively pulling back and arching the lower back.

- The Fix: Finish the movement by squeezing your glutes until your hips are fully extended. Stand tall and proud; do not lean back.

Your deadlift setup checklist: 5 steps to a perfect pull

- Stance: Approach the bar so it dissects the middle of your feet. Place your feet about hip-width apart.

- Grip: Hinge down and grip the bar just outside your shins without bending your knees yet.

- Shins to Bar: Without letting the bar roll forward, bend your knees until your shins touch the bar.

- Chest Up, Back Flat: Drop your hips, pull your chest up, and pull the slack out of the bar to create tension. Your back should be flat like a tabletop.

- The Pull: Take a deep breath, brace your core, and drive the floor away with your legs, dragging the bar up your body.

Step 4: Performance and recovery: applying physiology to break through plateaus

Understanding your engine: how to train your 3 energy systems

Your body has three distinct energy systems that it uses to fuel activity. The three energy systems are the ATP-PC system (for short bursts), the glycolytic system (for medium-duration effort), and the oxidative system (for long-duration endurance). Training with purpose means targeting the right system for your goals.

| Energy System | Duration | Used For | How to Train | Work:Rest Ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ATP-PC | 0-10 seconds | Max-effort lifts (1-3 reps), short sprints | Heavy strength training, 60m sprints | 1:12 |

| Glycolytic | 30s – 2 min | Typical bodybuilding (8-12 reps), 400m run | Hypertrophy training, HIIT | 1:3 |

| Oxidative | > 3 minutes | Long-distance running, cycling, hiking | Steady-state cardio | 1:1 or less |

The “Aerobic Paradox” in Strength Training

Most dedicated lifters live comfortably in the first two zones. You rely on the ATP-PC system when you hit a heavy triple, and you tax the glycolytic system when you chase the “pump” in a set of 12. Because these systems power the actual lift, it is easy to assume they are the only ones that matter for muscle growth. However, completely neglecting the third system, the oxidative pathway. This is a critical error that limits your total workload.

While your aerobic engine doesn’t power the heavy squat itself, it is the system responsible for refueling you between sets. The oxidative system is what replenishes your ATP stores and clears metabolic waste products while you rest. If you have a weak aerobic base, your body struggles to recharge efficiently, meaning you enter your next set partially depleted.

If you find yourself gasping for air two minutes after a heavy lift, or if your strength drops off significantly by your third or fourth set, your bottleneck isn’t your strength; it is your conditioning. Building a respectable aerobic base ensures you recover faster, allowing you to maintain high-quality output for the entire duration of your workout.

Periodization 101: structuring training for long-term success

Periodization is the logical, long-term planning of your training to avoid plateaus and peak at the right time. Instead of doing random workouts, you follow a structured plan that manipulates volume and intensity over time.

A simple linear periodization model might look like this:

- Phase 1 (4 weeks): Hypertrophy. High volume, lower intensity (e.g., 3-4 sets of 10-12 reps).

- Phase 2 (4 weeks): Strength. Medium volume, medium intensity (e.g., 4-5 sets of 4-6 reps).

- Phase 3 (4 weeks): Peaking. Low volume, high intensity (e.g., 3-5 sets of 1-3 reps).

This structured approach is a core principle used in elite athletic preparation and is supported by leading organizations like the American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM).

The science of muscle growth: mechanical tension, damage, and metabolic stress

Muscle growth (hypertrophy) is driven by three main mechanisms:

- Mechanical Tension: This is the primary driver. It refers to the force placed on the muscle when you lift a heavy weight through a full range of motion. This is where progressive overload is key.

- Metabolic Stress: This is the “pump” feeling you get from higher-rep sets where metabolites build up in the muscle. This cellular swelling can also signal growth.

- Muscle Damage: These are the microscopic tears in muscle fibers created during intense exercise, which signals the body to repair them stronger than before. This is what causes delayed onset muscle soreness (DOMS).

- Optimizing this repair process is a key area of sports science. I actually explored this in depth during my university research with athletes from the Stirling Clansmen, where we investigated if high-nitrate beetroot juice could outperform a placebo in accelerating recovery from this specific type of muscle damage.

An effective training program will strategically incorporate all three mechanisms, for example by including heavy compound lifts (tension), controlled eccentric movements (damage), and higher-rep isolation exercises (metabolic stress).

Beyond the gym: the physiological impact of sleep and nutrition on recovery

You don’t build muscle in the gym; you create the stimulus for it. The actual growth and repair happen while you recover.

- Sleep: This is when your body does most of its repair work. During deep sleep, your body releases growth hormone and manages cortisol (a stress hormone). Prioritizing 7-9 hours of quality sleep is non-negotiable if you want to make progress.

- Nutrition: You must provide your body with the raw materials to rebuild. This means consuming adequate protein to fuel muscle protein synthesis and sufficient carbohydrates to replenish the glycogen stores you used during your workout.

Step 5: The Dubai factor: adapting your training to heat and humidity

The physiological challenge: how heat impacts performance

Training in a hot and humid environment like Dubai presents a unique physiological challenge. When your body gets hot, it diverts a significant amount of blood flow to the skin to help cool you down through sweating. This means less blood, and therefore less oxygen, is available for your working muscles.

This process results in a higher heart rate for the same amount of work, faster depletion of your carbohydrate stores (glycogen), and rapid dehydration. The end result is quicker fatigue, reduced strength and endurance capacity, and a much higher perceived effort for any given workout.

Actionable hydration and electrolyte strategies for the Dubai climate

“Drink more water” isn’t enough. You need a specific strategy.

- Pre-hydration: Drink at least 500ml of water in the 2 hours leading up to your workout.

- During your workout: Aim to drink 200-250ml of fluid every 15-20 minutes.

- Electrolytes are crucial: Sweat isn’t just water; it contains electrolytes like sodium, potassium, and magnesium that are vital for muscle function. For any training session lasting longer than 60 minutes in the heat, you must replace them. My personal strategy is to add an electrolyte tablet to my water bottle during my workout to stay ahead of depletion.

Biomechanics and programming adjustments for training in the heat

- Reduce Volume and Intensity: During the hottest summer months, it’s wise to slightly decrease your overall training volume and avoid chasing one-rep maxes.

- Focus on Technique: Use the heat as an opportunity to focus on perfect biomechanics and neuromuscular efficiency with lighter loads.

- Time Your Workouts: Train during the cooler parts of the day, such as the early morning or late evening.

- Extend Rest Periods: Allow for longer rest between sets to give your heart rate more time to come down before you start your next set.

Recognizing the signs of heat stress and when to stop

You must prioritize safety over finishing a workout. Learn to recognize the signs of heat-related illness and have the discipline to stop.

Heat Exhaustion (Warning Signs):

- Dizziness or headache

- Nausea

- Profuse sweating and clammy, pale skin

- Rapid, weak pulse

Heat Stroke (Medical Emergency):

- Confusion or altered mental state

- High body temperature (above 40°C or 104°F)

- Hot, dry skin (lack of sweating)

- Rapid, strong pulse

Embrace a “safety first” culture. There is no shame in cutting a workout short to protect your health.

Your practical toolkit: technology, and analysis

Using your phone to analyze and improve your form

One of the most powerful coaching tools you have is already in your pocket. Record videos of your main lifts (squats, deadlifts, presses) from a side or 45-degree angle. Use your phone’s slow-motion playback feature to check for:

- Bar path: Is it a straight, vertical line?

- Joint angles: Are you hitting adequate depth in your squat?

- Back posture: Is your spine staying neutral throughout the lift?

This simple habit provides instant, objective feedback to accelerate your learning curve.

How wearable tech can (and can’t) help your training

Wearable devices (like Whoop, Garmin, or Apple Watch) are powerful tools for managing recovery in the Dubai heat. Tracking metrics like sleep quality and Heart Rate Variability (HRV) can give you valuable data on how well your body is recovering from stress.

However, it’s crucial to be transparent about their limitations. Metrics like “calories burned” are notoriously inaccurate estimates. No device can replace the importance of listening to your body. Use technology as a data point to inform your decisions, not as a dictator of your training.

Where to find your physical assessments

We have covered the technology, but what about testing your body’s physical limits? To access the specific instructions for the Knee-to-Wall Ankle Test, Thoracic Wall Angel, and Glute Bridge Test, refer to the comprehensive assessment section in my Proven Science of Pain-Free Training guide.

Putting it all together: a sample weekly training split

This 4-day upper/lower split incorporates the principles of strength, hypertrophy, and mobility discussed throughout this guide.

| Day | Focus | Key Exercises |

|---|---|---|

| Day 1 | Lower Body (Strength) | Warm-up: Ankle mobility, glute bridges. Workout: Barbell Back Squats (5×5), Romanian Deadlifts (3×8), Walking Lunges (3×10 per leg). |

| Day 2 | Upper Body (Strength) | Warm-up: Wall angels, band pull-aparts. Workout: Bench Press (5×5), Bent-Over Rows (3×8), Overhead Press (3×8). |

| Day 3 | Active Recovery | Mobility work, light cardio (walking or cycling). |

| Day 4 | Lower Body (Hypertrophy) | Warm-up: Hip 90/90s, bodyweight squats. Workout: Leg Press (3×10-12), Leg Curls (3×12-15), Leg Extensions (3×12-15). |

| Day 5 | Upper Body (Hypertrophy) | Warm-up: Thoracic windmills, face pulls. Workout: Dumbbell Incline Press (3×10-12), Lat Pulldowns (3×12-15), Lateral Raises (3×15). |

From theory to practice: becoming your own best coach

You now have the knowledge that forms the foundation of intelligent, effective training. We’ve moved from the core principles of biomechanics and physiology to the practical application of building an injury-proof body. You’ve learned how to break down and master the squat and deadlift, and you have specific strategies to optimize your performance and recovery right here in Dubai.

You hold the playbook to bridge the gap between knowing and doing. This guide empowers you to move beyond guesswork and train with scientific purpose. The journey to a stronger, more resilient body is built one smart repetition at a time. Start applying these principles, be patient with the process, and become your own best coach.

Ready to apply these principles with expert guidance?

Frequently asked questions (FAQs)

What is the kinetic chain in fitness?

The kinetic chain in fitness refers to the series of interconnected joints and muscles that work together to produce movement, where movement in one part affects all others.

How does biomechanics prevent injuries?

Biomechanics is the study of how forces interact with the human body. In fitness, it prevents injuries by optimizing leverage and joint angles to distribute stress onto muscles rather than connective tissue.

What are the three energy systems in exercise?

The three energy systems are the ATP-PC system for immediate, high-power movements (under 10 seconds), the glycolytic system for moderate-power efforts (up to 2 minutes), and the oxidative system for long-duration, low-power endurance activities.

How does muscle adapt to exercise?

Muscle adapts to exercise primarily through a process called hypertrophy, where resistance training causes micro-damage to muscle fibers, which the body then repairs and rebuilds to be stronger and larger to handle future stress.