There is a massive difference between lifting weights and building muscle.

You’re putting in the work. You’re in the gym consistently, you’re pushing yourself, but the scale isn’t moving and your measurements are stuck. Muscle growth has stalled, and it’s frustrating. If you’re tired of the endless cycle of “bro-science,” conflicting advice, and program-hopping, you’ve arrived at the right place. The fitness world is noisy, but the science of muscle growth is clear. The problem isn’t your effort; it’s the lack of a scientific framework.

It’s time to stop renting the weights and start training with intent. This guide is not just another list of exercises; it is the definitive biological blueprint for Hypertrophy. Whether you are a bodybuilder, an athlete looking to improve performance, or a regular gym-goer wanting to fill out your t-shirt, we are about to replace “guesswork” with “mechanisms” to ensure every rep translates into tangible growth.

This article is the definitive scientific blueprint you’ve been searching for. We will translate the complex cellular mechanisms that trigger muscle growth, specifically the concepts of myofibrillar and sarcoplasmic hypertrophy, into an actionable, evidence-based protocol. As a Sports Science graduate with over 15 years of coaching experience, I specialize in helping lifters just like you move past frustrating plateaus by applying this science. It’s time to stop guessing and start building.

What is Hypertrophy?

Before we pick up a weight, we need to define our terms. In the context of this guide, hypertrophy refers specifically to muscle hypertrophy, the enlargement of muscle mass caused by resistance training.

It is crucial not to confuse Hypertrophy with Muscular Strength.

- Muscular Strength is the ability of a muscle or group to exert maximal force in a single effort (think: a 1-rep max powerlifter). This is usually trained with heavy loads and low repetitions.

- Hypertrophy is the physiological growth of the muscle cells themselves (1).

While getting stronger often leads to bigger muscles, and bigger muscles have the potential to be stronger, they produce different physiological responses. If your goal is size, your program must reflect that.

A Note on “Hyperplasia”

You may have heard the term hyperplasia. This refers to an increase in the actual number of muscle fibers, whereas hypertrophy is the increase in the size of existing fibers.

While hyperplasia has been observed in animals, its role in humans is murky. Evidence suggests it may only occur in humans who have reached their absolute upper genetic limit or those using performance-enhancing drugs (1). For 99% of the population, muscle growth is purely a result of hypertrophy, not hyperplasia.

The Flip Side: Understanding Atrophy

As illustrated in the diagram above, muscle tissue exists on a sliding scale. The process of building muscle is Hypertrophy (moving to the right), but the process of losing it is Atrophy (moving to the left).

It is important to understand that muscle tissue is metabolically expensive; it costs your body a lot of energy to maintain. If you stop providing the stimulus (resistance training) or the fuel (protein), your body will efficiently strip that muscle away to save energy. In sports science, we call this the “Use it or Lose it” principle. Your goal with this guide is to keep the arrow pointing to the right.

Who Needs Hypertrophy?

Hypertrophy is most famously associated with bodybuilding, a sport where success is judged strictly on the size, symmetry, and quality of muscle tissue.

However, writing hypertrophy off as purely “aesthetic” is a mistake. Increased muscle mass is a necessity for athletic performance. You only need to look at the physiques of elite athletes to see the pattern:

- Cristiano Ronaldo (Football longevity)

- Anthony Joshua (Boxing power)

- LeBron James (Basketball durability)

- Mat Fraser (CrossFit dominance)

The list goes on, but the point remains: muscle mass is a determining factor for success. Furthermore, for the general population, maintaining muscle mass is critical for longevity, metabolic health, and injury prevention. Whether you are chasing a stage trophy or just chasing a better version of yourself, understanding how muscle grows biologically allows us to now examine the specific factors that trigger this growth.

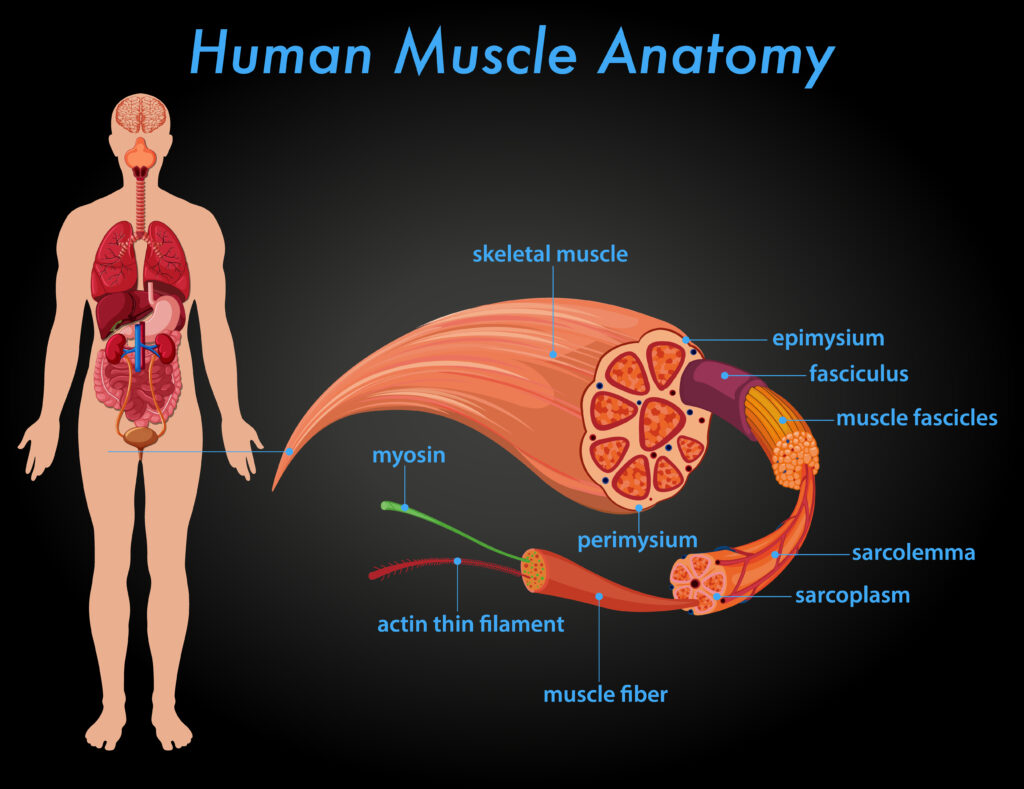

Anatomy 101: The Structure of Skeletal Muscle

Think of your muscle like a massive, industrial-strength fiber-optic cable. It is a structure within a structure within a structure. Here is the hierarchy of the hardware, moving from the outside in:

- The Muscle Belly (The Whole Package): This is what you see in the mirror (e.g., the Biceps Brachii). The entire muscle is wrapped in a sheath of connective tissue called the Epimysium.

- The Fascicle (The Bundle): If you slice the muscle open, you will see bundles of fibers grouped together. These bundles are called Fascicles. They are wrapped in their own connective tissue called the Perimysium.

- The Muscle Fiber (The Cell): Inside each fascicle are the actual muscle cells, known as Muscle Fibers. These are wrapped in a membrane called the Sarcolemma.

- Sarcoplasm: Just as a normal cell has cytoplasm, a muscle fiber is filled with a fluid called Sarcoplasm. This fluid contains glycogen, fats, and the mitochondria (energy plants) needed to fuel contraction.

- The Myofibril (The Rods): This is where the magic happens. Inside every muscle fiber are hundreds to thousands of rod-like strands called Myofibrils. These are the contractile threads that run the length of the fiber.

- The Sarcomere (The Engine Room): If you zoom into a myofibril, you find the smallest functional unit of a muscle: the Sarcomere. This is composed of two protein filaments:

- Actin (Thin Filament): The rope.

- Myosin (Thick Filament): The hands that pull the rope.

Why This Matters for Hypertrophy

Understanding this structure explains why we train the way we do. We are trying to mechanically stress these internal filaments to force the body to thicken the cable.

The Mechanics of Muscles Growth

Muscle growth isn’t random. It is a specific biological adaptation to the stress you impose on your body through resistance training.

The Mechanism:

- The Overload: Training causes “overload” to the actin and myosin filaments.

- The Adaptation: Provided you have sufficient recovery and nutrition, the body repairs and regenerates these proteins.

- The Growth: To protect against future stress, the body expands and enlarges the actin and myosin, increasing the number of myofibrils within the fiber (2).

The Three Drivers of Growth

According to science, three specific factors induce this growth response. To maximize hypertrophy, your training should touch on all three:

1. Mechanical Tension (The Primary Driver)

This is the force created when a muscle contracts against resistance (11). It is the most critical factor. When your muscle fibers are exposed to this tension, specialized sensors (mechanoreceptors) detect the force and kick off a chemical cascade (mTOR pathway) to build new muscle protein. If you never increase the load (weight), you stop creating enough tension to force adaptation.

2. Muscle Damage

This is the localized damage to muscle tissue (microtears) caused by intense training (13). The body’s inflammatory response repairs this damage, often making the tissue stronger. Eccentric contractions (lowering the weight) cause the most damage.

- Note: Excessive muscle damage can actually hinder progress. Soreness is not a reliable indicator of a good workout. Focus on creating tension, not just annihilating the muscle.

3. Metabolic Stress (The Pump)

This is the “burn” you feel during high-rep sets. It is the accumulation of metabolites (lactate, hydrogen ions) during anaerobic exercise (14). This environment causes cellular swelling, which signals the cell to reinforce its structure and grow. This is why bodybuilders often use moderate weights with short rest periods.

The Nutrition Factor

You cannot out-train a diet that doesn’t support growth. While genetics play a massive role (some people simply grow easier than others due to DNA (6)), you can maximize your genetic potential with two things: Calories and Protein.

Energy Balance

To build tissue, you generally need a positive energy balance. You must consume more energy than you expend (7). While it is possible to gain muscle in a deficit, it is significantly harder because the body’s anabolic (building) response is blunted (6). This is just a summary. For a deep dive into calculating your exact macros, read my Performance Nutrition Guide.

Protein: The Building Block

Protein is non-negotiable. For hypertrophy to occur, you must achieve a state of positive net balance—where muscle protein synthesis exceeds muscle protein breakdown.

This fundamental mechanism was extensively mapped out in the landmark paper Exercise, protein metabolism, and muscle growth (7), co-authored by my mentor, Professor Kevin Tipton.

In Memoriam:

- I had the distinct privilege of studying under Professor Kevin Tipton during my time at the University of Stirling, where he served as my lecturer and Dissertation Supervisor. His groundbreaking research on protein metabolism forms the backbone of the nutritional recommendations in this guide.

- The sports science community lost a true pioneer when Kevin passed away on January 9th, 2022. This guide honors his legacy by ensuring his evidence-based principles continue to educate and help athletes grow.

How much? Research recommends 1.7g to 2.0g of protein per kilogram of body weight daily (6).

- Example: A 70kg individual needs between 119g and 140g of protein per day.

Frequency: Spacing this intake out is optimal. Aim for 3–4 meals, each containing at least 25g of protein, spaced every 5–6 hours.

Leucine: After a workout, consuming protein rich in the amino acid Leucine (3-4g) is beneficial to “kick start” protein synthesis (10).

Expert Tip for Dubai Lifters: You don’t always need to cook at home to hit these numbers. A standard Shish Tawook platter is a goldmine for lean protein, and Camel meat (available at local butchers) is actually leaner than beef. Just be mindful of the garlic sauce (toum) if you are watching your calorie limits.

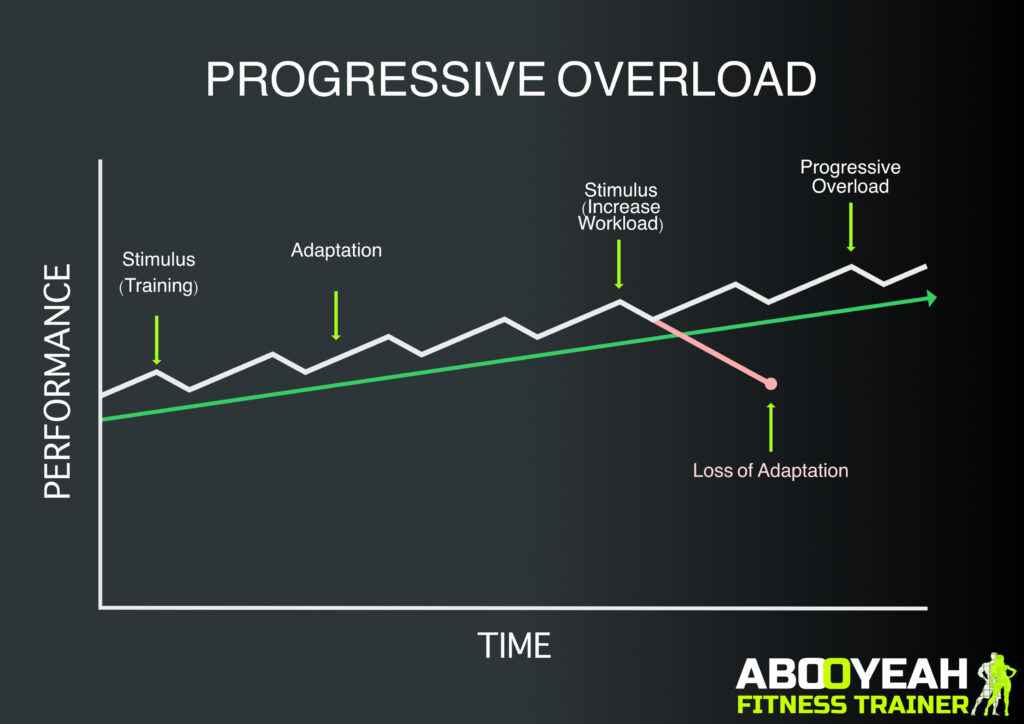

The Governing Law: Progressive Overload

Understanding Mechanical Tension, Muscle Damage, and Metabolic Stress is useless if you do not apply the fundamental law of training: Progressive Overload.

The human body is an adaptation machine. It does not want to carry extra muscle tissue; muscle is metabolically expensive to maintain. If you bench press 60kg for 10 reps today, and do the exact same thing next week, your body has no stimulus to grow.

To force continuous growth, the training stimulus must increase over time. This is the practical application of the adaptation principles we covered in my Mastering Progressive Overload: The Science of Periodization & Continuous Growth guide.

The 4 Ways to Overload for Hypertrophy

Most people think overload just means “adding weight.” While that is valid, it is not the only way, and for hypertrophy, it isn’t always the best way.

- Increase Intensity (Load): Adding weight to the bar. (e.g., 60kg → 62.5kg). Best for Mechanical Tension.

- Increase Volume (Reps/Sets): Doing more work with the same weight. (e.g., 3 sets of 10 → 3 sets of 12). Best for Metabolic Stress.

- Improve Density: Doing the same work in less time (shortening rest periods). Increases metabolic demand.

- Improve Technique (The “Quality” Overload): Performing the same rep with a slower tempo, a harder squeeze, or a greater range of motion.

Pro Tip: For hypertrophy, I recommend mastering a weight before increasing it. If you can squirm and twist your way through 10 reps, don’t add weight. “Overload” your form first. Make the 10 reps look perfect. That is a stronger stimulus for growth than adding 5kg of ego.

Decoding the two types of hypertrophy: myofibrillar vs. sarcoplasmic

“Muscle growth” is not a single, monolithic process. How your muscles grow can be just as important as how much they grow, especially when your goals are tied to both strength and aesthetics. The two primary types of hypertrophy are myofibrillar and sarcoplasmic, and understanding the difference is key to breaking through plateaus.

Type A: Myofibrillar Hypertrophy: (Building Denser, Stronger Muscle)

What it is: The growth of the contractile parts of the muscle fiber. Think of your fibers as being made up of tiny protein strands called actin and myosin (the “myofibrils”) that slide past each other to create contraction. This adaptation increases the number and thickness of these strands.

- Primary outcome: A direct increase in the muscle’s ability to produce force. This leads to significant gains in maximal strength and creates a harder, denser-looking muscle.

- How to train for it: This responds best to high mechanical tension. Use heavy loads and lower repetition ranges (typically 4–8 reps) with full recovery periods.

Type B: Sarcoplasmic Hypertrophy: (Increasing Muscle Volume and Fullness)

What it is: An increase in the volume of the sarcoplasm, the fluid-like substance that surrounds the myofibrils. This involves increasing non-contractile elements like glycogen (stored carbs), water, and minerals within the cell.

- Primary outcome: A significant increase in the overall size and volume of the muscle, giving it a “fuller” or “pumped” appearance. This is often associated with the classic “bodybuilder” physique.

- How to train for it: This responds best to high metabolic stress. Use moderate-to-high repetition ranges (typically 10–20 reps) with shorter rest periods to maximize cellular swelling.

The scientific synergy: why you need both

It’s important to understand that these two types of growth are not mutually exclusive. Nearly all forms of resistance training will stimulate both to some degree.

However, you can and should emphasize one over the other based on your programming block. While some researchers debate the long-term contribution of purely sarcoplasmic growth, for the lifter whose goal is maximum size, it is an undeniably critical tool. A truly effective training plan will strategically periodize both: using heavy blocks to build density (Myofibrillar) and volume blocks to maximize size (Sarcoplasmic).

Programming for Hypertrophy

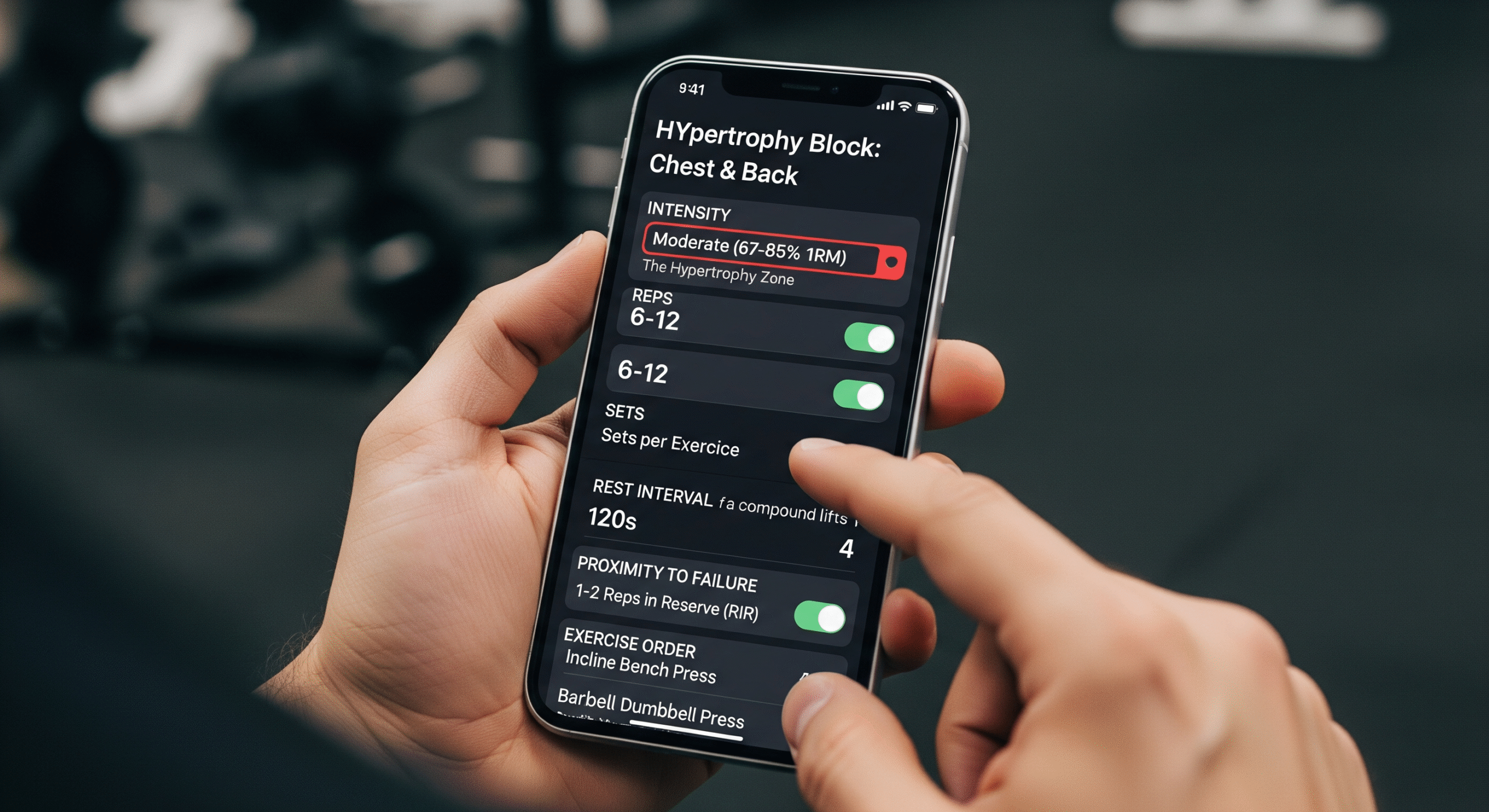

This is where the rubber meets the road. How do you structure a workout to hit the “sweet spot” of mechanical tension and metabolic stress?

1. Intensity (The Load)

Intensity in weightlifting is defined by your % of 1-Rep Max (1RM).

- Heavy (+85% 1RM): Great for tension, but low reps mean low metabolic stress.

- Light (<65% 1RM): Great for metabolic stress, but recruitment of high-threshold motor units is lower.

- Moderate (67-85% 1RM): The Hypertrophy Zone. This range allows for heavy enough weight to create tension, but enough reps to create metabolic stress (1).

If you are completely new to the gym, jumping straight into an advanced split might be too much. Start with my 12-Week Beginner Roadmap to build your foundation first.

2. Repetitions

Because we are targeting that moderate intensity, the math dictates our rep range.

- 6 to 12 Reps: This is the gold standard. It provides the perfect intersection of time-under-tension and force production (6).

3. Sets and Volume

Volume (total work done) is highly correlated with hypertrophy.

- Sets per session: 3–6 sets per exercise is the NSCA recommendation (1).

- Sets per week: 10+ sets per muscle group per week is a solid starting point (Fry, A. C. (2004)).

- Note: This is individual. Some people grow on less; others need more. Start at 10 and adjust based on recovery.

4. Rest Intervals

How long should you rest between sets?

- The Science: Short rest (30-90 seconds) increases metabolic stress (the pump) and anabolic hormone release (2).

- The Reality: If you rest too little, your strength drops, and you cannot perform enough volume in subsequent sets.

- The Solution: Schoenfeld (2016) suggests that resting at least 2 minutes is often superior because it allows you to maintain the weight and volume needed for mechanical tension (6).

- My Advice: Use 2+ minutes for big compound lifts (Squats, Bench) and 60-90 seconds for smaller isolation lifts (Curls, Raises).

5. Failure and Effort

Should you train to failure (until you cannot do another rep)?

Evidence suggests failure promotes hypertrophy, but it comes at a cost of fatigue and potential overtraining (Helms, E. R., et al. (2014)).

- Strategy: Take some sets to failure, but not all. Keep 1-2 reps “in the tank” on heavy compound movements to ensure safety and manage fatigue.

6. Exercise Selection & Order

- Variety: Use both free weights (for stabilizer activation) and machines (for stability and targeting specific muscles).

- Order: Unlike strength training, where the “biggest” lift always comes first, hypertrophy training focuses on lagging body parts. If your biceps are your weak point, prioritize them by placing them earlier in the workout when you are fresh (6).

Sample Workouts

There is no single “best” program, but a common and effective split is Push / Pull / Legs. This ensures every body part is hit with sufficient frequency and volume.

Below are sample sessions applying the principles of 6-12 reps, moderate loading, and mixed exercise selection.

A Note on Equipment:

Dubai is home to some of the best bodybuilding gyms in the world (like Binous or Warehouse Gym). If you have access to specialized machines like a Hack Squat or a Prime Plate-Loaded Row, feel free to swap the free-weight versions below for these machines. They offer excellent stability, allowing you to push closer to failure safely.

Workout A: Upper Body (Push Focus)

Targeting: Chest, Shoulders, Triceps

| Exercise | Sets | Reps | Rest | Notes |

| Barbell Bench Press | 4 | 6-8 | 2-3 min | Heavy Compound / Mechanical Tension focus |

| Incline Dumbbell Press | 3 | 8-10 | 2 min | Target upper clavicular pecs |

| Seated Dumbbell Shoulder Press | 3 | 8-12 | 2 min | Full range of motion |

| Cable Fly / Pec Deck | 3 | 10-12 | 60-90s | Constant tension / Metabolic Stress |

| Lateral Raises | 3 | 10-15 | 60s | Target side delts |

| Tricep Rope Pushdowns | 3 | 10-12 | 60s | Isolation / Squeeze at bottom |

Workout B: Upper Body (Pull Focus)

Targeting: Back, Rear Delts, Biceps

| Exercise | Sets | Reps | Rest | Notes |

| Pull-Ups (or Lat Pulldown) | 4 | 6-10 | 2-3 min | Vertical Pulling strength |

| Bent Over Barbell Row | 3 | 8-10 | 2 min | Thickness of the back |

| Seated Cable Row | 3 | 10-12 | 90s | Focus on the squeeze |

| Face Pulls | 3 | 12-15 | 60s | Rear delt and rotator cuff health |

| Barbell Bicep Curl | 3 | 8-12 | 90s | Heavy bicep load |

| Hammer Curls | 3 | 10-12 | 60s | Brachialis/Forearm focus |

Workout C: Lower Body

Targeting: Quads, Hamstrings, Glutes, Calves

| Exercise | Sets | Reps | Rest | Notes |

| Barbell Back Squat | 4 | 6-10 | 3 min | The king of leg builders |

| Romanian Deadlift (RDL) | 3 | 8-10 | 2-3 min | Hamstring/Glute hinge movement |

| Leg Press | 3 | 10-12 | 2 min | High volume without spinal loading |

| Leg Extension | 3 | 12-15 | 60-90s | Quad isolation / Metabolic stress |

| Lying Leg Curl | 3 | 10-12 | 60-90s | Hamstring isolation |

| Standing Calf Raise | 4 | 10-15 | 60s | Don’t neglect the calves! |

Hypertrophy Summary (Cheat Sheet)

| Variable | Target |

|---|---|

| Intensity | 67–85% 1RM |

| Reps | 6–12 |

| Sets | 10–20 per muscle per week |

| Rest | 2 min compounds, 60–90s isolations |

| Frequency | 2x per muscle/week |

| Protein | 1.7–2.0 g/kg/day |

Conclusion

Hypertrophy is a science, but it requires an artist’s application. You cannot change your genetics, but by manipulating intensity (67-85%), volume (10+ sets), and recovery, you can maximize the potential of the physique you were born with.

Remember, this is a process of adaptation. You must give the body a reason to grow (training) and the resources to do so (nutrition). Be patient, apply these principles consistently, and enjoy the process of building a stronger, more muscular version of yourself.

Expert FAQ: Your Top Questions on Muscle Hypertrophy

What is the simple definition of muscle hypertrophy?

Muscle hypertrophy is the physiological increase in the size of skeletal muscle fibers. It occurs when the body repairs muscle fibers damaged during resistance training by fusing them with new protein strands, making the muscle thicker and stronger. It is distinct from Hyperplasia, which would be an increase in the number of fibers.

What is the difference between hypertrophy vs. strength training?

The main difference lies in the goal and the rep range. Strength training (1-5 reps) focuses on the neurological ability to exert maximal force (moving weight from A to B). Hypertrophy training (6-12 reps) focuses on physiological structural change (exhausting the muscle fiber to force growth). While they overlap, strength is about efficiency, while hypertrophy is about volume.

What is the difference between hypertrophy and atrophy?

They are biological opposites. Hypertrophy is the growth of muscle tissue due to mechanical stress (training) and sufficient nutrition. Atrophy is the wasting away or decrease in muscle size, usually caused by inactivity (“use it or lose it”), injury, or a caloric deficit.

Hypertrophy vs. Hyperplasia: Can you actually increase the number of muscle fibers?

For 99% of humans, the answer is no. Hypertrophy increases the size of your existing fibers. Hyperplasia is the splitting of fibers to create newones. While seen in some animal studies, there is very little evidence that hyperplasia makes a significant contribution to muscle growth in humans without the use of performance-enhancing drugs.

What is hypotrophy compared to hypertrophy?

While they sound similar, they describe different states. Hypertrophy is the over-development or growth of tissue (what bodybuilders want). Hypotrophy (often referred to medically as underdevelopment) refers to tissue that failed to develop to its full size potential, often due to genetic or nutritional issues.

Is 3 days a week enough for hypertrophy?

Yes, provided the volume is sufficient. A 3-day “Full Body” split allows you to hit every muscle group 3 times per week. As long as you achieve 10-20 hard sets per muscle group per week, you can trigger significant hypertrophy on a 3-day schedule. Frequency is a tool to manage volume, not a magic requirement.

Does soreness mean I achieved hypertrophy?

No. Soreness (DOMS) is a sign of Muscle Damage, which is just one of the three drivers of growth. It is entirely possible—and often preferable—to stimulate growth via Mechanical Tension (heavy weight) and Metabolic Stress (the pump) without being too sore to walk the next day. Chasing soreness often leads to under-recovery, not more muscle.

References

- National Strength and Conditioning Association (NSCA). Basics of Strength and Conditioning Manual.

- Schoenfeld, B. J. (2010). The mechanisms of muscle hypertrophy and their application to resistance training. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research.

- Schoenfeld, B. J. (2013). Potential mechanisms for a role of metabolic stress in hypertrophic adaptations to resistance training. Sports Medicine.

- Antonio, J., & Gonyea, W. J. (1993). Skeletal muscle fiber hyperplasia. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise.

- Slater, G. J., et al. (2019). Is an energy surplus required to maximize skeletal muscle hypertrophy associated with resistance training? Frontiers in Nutrition.

- Tipton, K. D., & Wolfe, R. R. (2001). Exercise, protein metabolism, and muscle growth. International Journal of Sport Nutrition and Exercise Metabolism.

- Norton, L. E., & Layman, D. K. (2006). Leucine regulates translation initiation of protein synthesis in skeletal muscle after exercise. The Journal of Nutrition.

- Clarkson, P. M., & Hubal, M. J. (2002). Exercise-induced muscle damage in humans. American Journal of Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation.

- Tesch, P. A., et al. (1986). Muscle metabolism during intense, heavy-resistance exercise. European Journal of Applied Physiology and Occupational Physiology.

- Schoenfeld, B. J., et al. (2017). Dose-response relationship between weekly resistance training volume and increases in muscle mass: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Sports Sciences.